For Services Offered and Prices, Please Navigate to the Services Offered and Fees Page.

Birds

Different species of birds exhibit a wide range of intelligence, functional levels and needs. I provide everything from basic care visits for your little songbirds, like canaries and finches, to hybrid visit/sits or full bird sitting for hookbills, such as parrots, cockatoos and macaws, and corvids, such as crows, ravens and jays.

I have had some very interesting experiences with birds over the years.

The area of Southern California where I grew up was near mountain foothills and canyons, with lots of trees and cliffs. Young birds of all sorts were always falling out of nests or fledging too soon. This has resulted in many of them coming into my care.

Raptors

I don’t provide care services for raptors. A falconry license or raptor rehabilitation permit is required for such care, and I don’t have appropriate facilities. Additionally, the amount and type of care required would significantly limit my ability to provide care services for other animals. Fortunately, if you’re a falconer with raptors, and need to take a vacation, you certainly know other falconers who can help you out. If you’ve found, or otherwise come into possession of a raptor, and need help with it, I can locate and refer you to a falconer or raptor rehabilitator.

Some Experiences with Raptors

One year when I was in junior high, I happened to find a young barn owl that was out of the nest way too early. Its flight feathers had only just begun to emerge, being only about a half inch long, looking sort of like large pin feathers. It was really a baby. I couldn’t see any nesting hole in any tree in the area and had no idea where it had come from. There were no adult owls around. So I took it home. That was my first experience with a raptor. At the time, I couldn’t locate a falconer in the area or anyone else who cared for raptors. In those days, there was no Internet to search and there were no such listings in the phone book. The local animal shelter said they got them all the time and had no choice but to euthanize them, which I, of course, thought was terrible.

So I immersed myself in studying up on the needs of raptors, specifically barn owls. Again, no Internet, so this meant spending a lot of hours in the library. I successfully raised the owl to adulthood. When it was old enough, I set up an outdoor cage and started leaving it there, increasingly with the door open. It gradually started flying around, but always came back for its mice. I started tossing mice out so it had to catch them. It started flying further off and returning less frequently until it eventually returned to the wild.

My friend, who owned a popular local pet shop, knew of my experience, so the staff began to give me all the juvenile barn owls people brought in. There were also a couple of other owl species, several kestrels and a red-tailed hawk. It started to be quite a burden, but it was also very satisfying. Fortunately, I finally found a couple of certified raptor rehabilitators in cities not too far away, so told the pet shop to begin calling them.

I thought about getting a falconry license, but decided it was too much of a commitment at the time. Plus, there was no space at my home to build a proper mews.

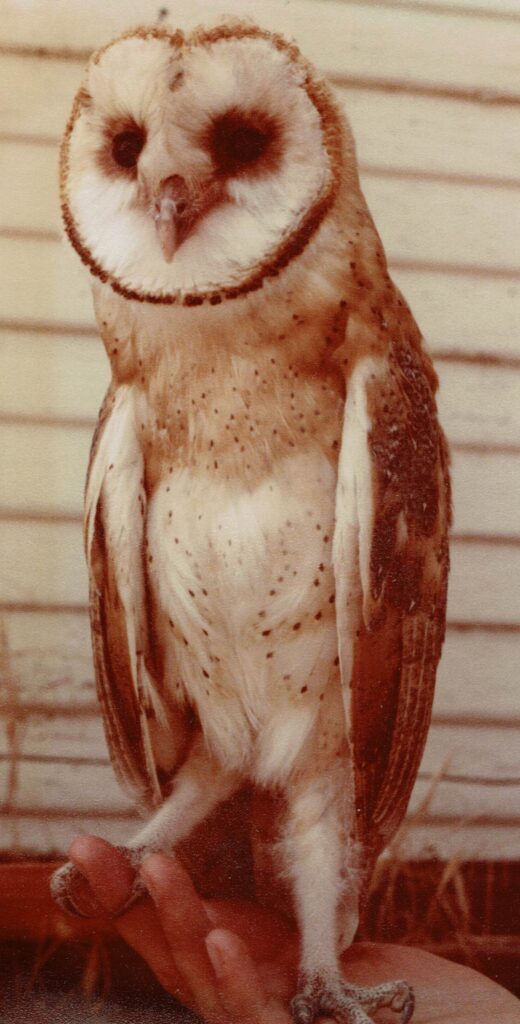

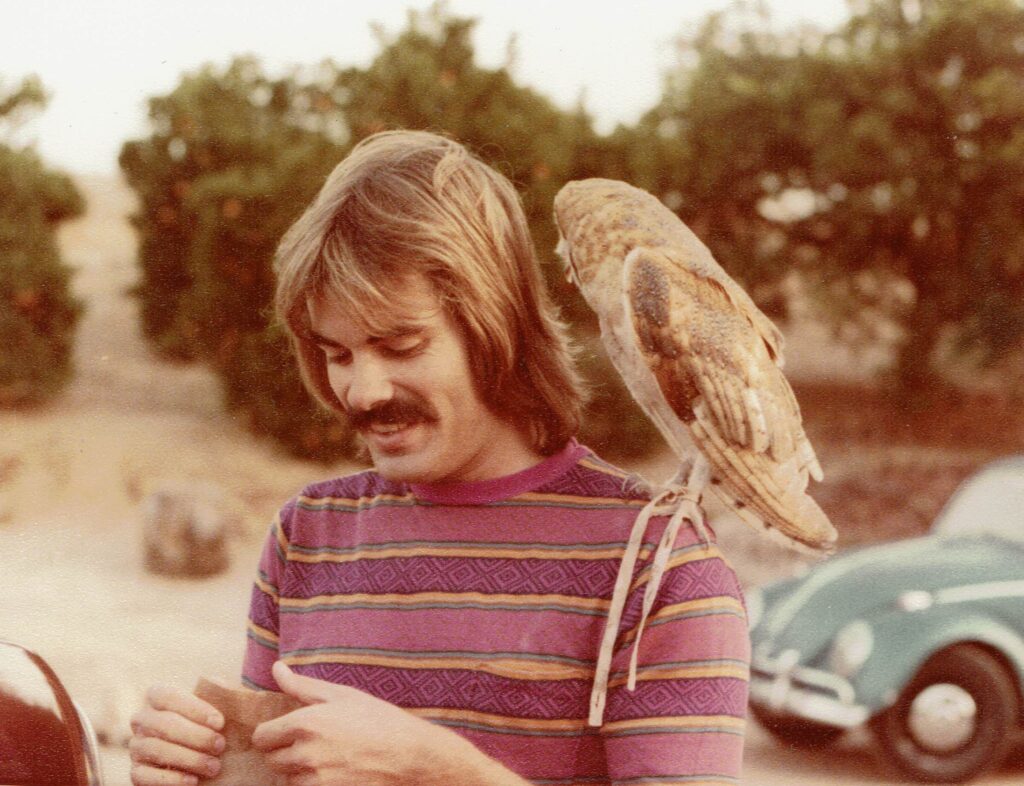

Sweetheart, A Barn Owl

Many years later, around 1976, I happened to find another barn owl chick while hiking. I brought it home to do the usual care program that I had used to do. I had never named any of the raptors I cared for during those earlier years, as I planned to release them as soon as possible and didn’t want to become attached. But I guess I had become a little more sentimental or stupid or something as I was growing older, because I did become attached to this barn owl, who, as she grew and feathered out, turned out to be a female. I named her Sweetheart.

Sweetheart was with me for about a year, and I loved caressing her, letting her nibble on my finger or ear, flying her and showing her off to my friends, who had never before seen a barn owl close-up, and were always amazed at how strikingly beautiful they are, how soft their feathers are and how quiet their flight is.

But I finally managed to shake off the desire to keep her as a pet and did the same kind of gradual reintroduction to the wild that I used to do with the other barn owls. With Sweetheart, it was actually pretty easy. There was a male barn owl that had a territory around the home where my friends with the male raccoon lived. (See the Miriah story on the Wild and Exotic Pets page.) Around dusk, he would begin his patrol. We could hear his calling and see his bright white underside flying around. I took Sweetheart to their house for several nights and we sat outside and listened for him. Sweetheart was very aware of, and interested in, him. One evening, she took off from my shoulder and flew up toward him. They began “playing” in the sky and flew off together. From then on, we could occasionally enjoy seeing them both flying around and calling. It was great.

Hookbills

I had several friends who owned various species of parrots, cockatoos and macaws. From interacting with their birds, I learned just how incredibly intelligent, social and emotional these amazing hookbills are. One of my friends had a large, beautiful ranch, where he bred many species of hookbills. He was a major supplier of African grey parrots to the pet trade.

If you think humans are the only sentient creatures on earth, you’re mistaken. If you think humans are the only species that can use language, you’re also mistaken about that. It takes two things to be able to use language – a highly-developed brain with the right components, and the physical vocal ability to produce the complex sounds of language. Some hookbills have both. The supreme example is the African grey parrot. I suggest you watch the PBS Nova episode, Bird Brain, which originally aired in 2017.

I have interacted with many kinds of hookbills and cared for many friends’ hookbills, of many species. You can feel very comfortable leaving your loved, valuable bird in my care.

My Crows, Smudge and Iktomi

Hookbills are so beautiful and intelligent, not to mention talkative in many cases, that, as a teenager, I was very tempted to see about getting one. However, I recognized that I wasn’t mature and responsible enough to take on the serious commitment of owning an animal with a lifespan longer than many humans and the constant needs of a two-year-old human child.

Little did I know that I was destined to have such a bird anyway. As I point out on the Wild and Exotic Pets page, people typically don’t set out to own a wild species. It usually just sort of happens. This was the case with my crows. We had several very large trees in our yard, where crows would nest. Every year, one or two would inevitably fall out of the nests or fledge way too early. My practice was to put them up on a protected area of our house roof, where the parents would continue to care for them. They wanted absolutely nothing to do with a human and were happy to get away from me up there.

But one year, one of the juvenile crows didn’t respond normally. When I approached it, instead of trying to get away, it gaped its mouth at me, fluttered its wings and made that raspy squeal, begging to be fed. When I picked it up, it continued to beg. As usual, I took it up the ladder, onto the roof and placed it in the usual spot. I went back down the ladder. The next thing I knew, the crow had come to the edge of the roof, jumped back down onto the grass beside me, then resumed its begging. I tried putting it back onto the roof twice more, with no luck. The third time, I tried walking away, but the little bird just sat there, looking in my direction and squealing pathetically. I was dumbfounded. As with that original barn owl, I didn’t know what to do, so I ended up taking it into the house and setting it up in a box. And that, as they say, was that. It had taken ownership of me.

To this day, I have never had anyone who could give me a plausible, evidence/study-based explanation of such behavior. The accepted thinking is that juvenile birds imprint almost immediately after hatching on whatever figure they first see, typically the parent bird, and that once this imprinting has occurred, it is permanent. It cannot be changed. A couple of my bird friends have proposed a theory that perhaps there is some reason, or some rare anomaly in individuals, which allows or causes “reimprinting” on a new perceived source of comfort, or “parental” figure. I don’t know. But it happened twice, with Smudge and Iktomi – just two juvenile crows out of perhaps thirty to forty or so. I don’t know if it’s possible, but I would love to see a scientifically valid study to explore whether “reimprinting” is real or not. Perhaps there is some physiological or biochemical difference in such birds that causes the behavior.

I would later, through a blood test, confirm my feeling that the crow was a female. I named her Smudge. It is well-established that crows are one of the smartest creatures on earth, but simply knowing that fact gave me no clue to the incredible experience I was in for. They’re not just highly intelligent, but socially advanced as well. Being so intelligent and social means that they are in constant need of attention and mental stimulation, like dogs or cockatoos, so I had the commitment, whether I had wanted it or not. And for a long time. Crows don’t live as long as a bird like a cockatoo, but they do live a very long time.

Assuming avoidance of disease or injury, with proper diet and care, a captive crow can be expected to live to around thirty years of age, but they can get much older. The record I’ve seen noted is fifty-nine years. My crow, Iktomi, is only about sixteen years old at the time I’m writing this, so he’s only lived about half of his expected captive lifespan. He could outlive me, so I’ve made arrangements for his welfare if I go before he does.

I learned a tragic lesson from the death of my beautiful Smudge, who passed away at the too-young age of eighteen, due to West Nile virus disease. At the time, the particularly high susceptibility of crows to West Nile wasn’t widely understood, until a plague of it swept through Southern California, killing crows by the thousands. Like Smudge had, Iktomi has his outdoor cage, where he goes for fresh air, a little sunshine and contact with wild birds. But I’m a lot more careful not to allow him out during “mosquito hours” and, during certain high-mosquito months, he doesn’t go out at all.

Every crow is a distinct individual, with its own unique personality. Smudge was very affectionate. She loved to sit in my lap and have her feathers stroked and the back of her head and neck massaged. Whenever I tried to get up to work, do household chores, etc., she usually wasn’t ready to let me go. She would grab hold of my finger with her beak and hold on, giving me that “Oh no you don’t” look. I suppose you could say she was sort of dog-like in her need for affection. Iktomi is more cat-like. He wants attention, but on his terms. He seems to enjoy asserting his power, shunning me when I have time and want to interact, but coming over and demanding attention when I’m busy and it’s inconvenient.

Though each crow has its own personality, in general, they’re all sort of assholes. When you have a creature with super-high intelligence, a bad attitude and a sophisticated sense of humor, it can sometimes seem like you’re living with an evil genius. For instance, both Smudge and Iktomi were quickly able to identify all the little things – pens, zip drives, glasses, keys, TV remotes, etc. – that I need for working and just functioning, then, when I’m not watching, steal them and hide them. Iktomi gets great pleasure from watching me hunt for them, observing my frustration and agitation. He’ll sometimes be bolder, snatching my glasses off my face and flying off with them. He likes to take a piece of paper I need and rip it up. He likes to peck my ears and pull my hair. People think that birds can’t control their pooping, that they just do it whenever they need to, wherever they are. That’s not entirely true. Iktomi will sometimes hold his poop until I sit down to work. Then he’ll fly over, perch on my shoulder, immediately poop on my back, then quickly fly off to watch, from a safe distance, with glee, as I curse and have to change my shirt.

By the way, his name, Iktomi, comes from Sioux mythology; it is the name of a mischievous spirit, so it suits him. However, he won’t answer to that name, as I always just call him “birdie bird”. That’s what gets his attention. I once thought that Iktomi’s pranks were the result of not having enough activities to keep him mentally stimulated. So I bought more toys and came up with all kinds of mental puzzles to keep him entertained. He appreciated all that, but it didn’t diminish his enthusiasm for teasing me.

I’ve come to recognize all the complex components of crow perceptions, feelings, behavior and communication, as indicated by expressions, body movements and positions, feather control and, especially, vocalizations. Iktomi has no problem communicating his feelings, needs and wishes to me, and I have no difficulty understanding. There are some twenty-thirty different kinds of vocalizations that Iktomi uses with me. It’s hard to count all the different types and combinations. He also communicated with my dog and cat when they were alive. He combines various vocalizations with various body movements/positions for more precise communication. It may not qualify as language, but it is very sophisticated and precise communication.

Iktomi is my buddy. Even though he sometimes torments me, he’s mostly quite affectionate and I know he loves me. He’s like that best friend you have who just likes to pull practical jokes on you. If you love him and you know that the jokes make him happy, you put up with it.

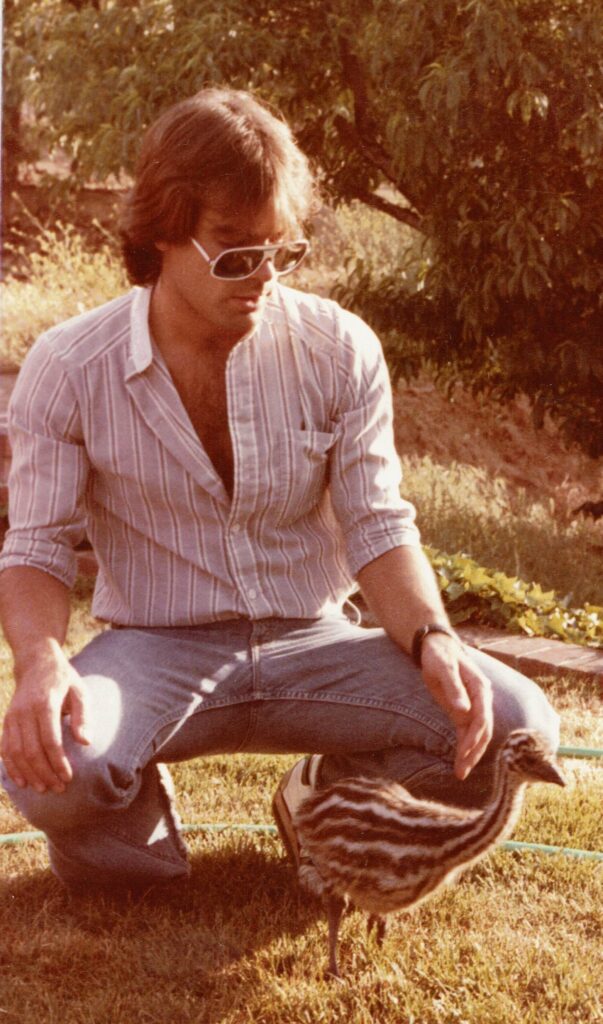

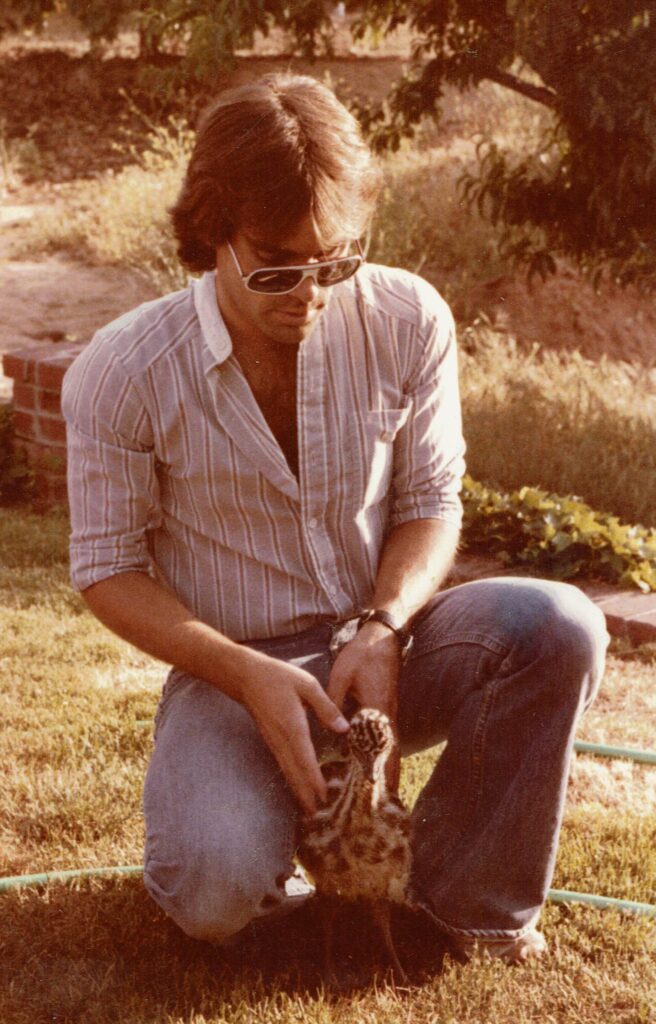

My Emu, Aussie

Back in the late 70s, I had a friend who worked at an animal park in Southern California. One day, he showed up at my house with an emu chick, only a couple days old. Apparently, the chick had presented with some balance/movement problems, and the staff had determined that it must have neurological damage. My friend had been assigned to euthanize it. Instead, he brought it to me. He suspected the condition wasn’t as the staff thought. He asked if I could take the chick and care for it. He knew I could never say no to anyone with an animal in need.

Thus began another amazing relationship I had with an exceptional animal, who I named Aussie, gaining more insight into the complex, wonderful nature of living things, which most people, unfortunately, never have the opportunity to understand. Aussie is one of the best representative cases ever of the concept I have, which I call levels of potential.

Emus are the second largest bird, by height, after the ostrich. Fortunately, I had a very large back yard, because I knew Aussie was going to grow up to be a huge individual – that was, if he was actually OK and not debilitated as the park staff had suspected. I don’t know what the staff had seen that indicated a problem, because Aussie seemed just fine to me. A couple of times, he miscalculated the height of a rock or other obstacle and stumbled over it, but what chick doesn’t make mistakes like that?

Aussie quickly imprinted on me and I became “daddy”. (With emus, it’s the father who cares for and protects the chicks. They won’t let any other animal, often even the mother, near them.) This imprinting, I assumed, was because the eggs were hatched in an incubator and Aussie never had a chance to see an emu parent, coming to live with me when just a day or two old. He was as gravitationally connected to me as the Moon is to the Earth. He followed me around everywhere, making his precious little peeping sounds. Besides the large back yard, I was also fortunate to have a very large, empty field across the street from my house. I had used to curse that fact, as the field was a source of gophers, which often moved from there into my yard, creating unsightly mounds of excavated soil. But now I was glad it was there.

I would take Aussie for long walks in the field, where he would peck at the many grasses, mallows, wild radish & mustard and other edible plants, as well as chasing down grasshoppers and other insects. Sometimes, he would get involved with something and not notice that he had fallen some distance behind me. When he realized it, he would come dashing after me, peeping at the top of his lungs. He was so damned cute. The plants and bugs were just supplemental food items, treats. While Purina and Mazuri made feeds for a surprising number of different animal species, I could not find a specific emu feed. So, I researched the nutritional needs of emus, that I could find, and other similarly omnivorous ratites (large land birds like ostriches, rheas, etc.) and formulated a feed for Aussie, a mixture of various other feeds which would provide everything he needed in the correct amounts. It was gratifying that he seemed to like it so much. He grew pretty rapidly into a skinny “teenager”. He loved to run, so I was again thankful for the large field across the street. He eventually began to show the characteristics of a male (I hadn’t been able to determine his sex when he was a chick), with the blue neck and “punk” hairstyle. I loved his large, beautiful amber eyes. They sort of glowed like embers in his black face.

Emus make a variety of sounds in various situations. They’re all modified versions, of varying intensity, pitch and pattern, of the basic emu guttural, airy rumbling produced deep in the throat. There’s a very intense, loud rumbling that sounds very much like a lion’s loud growling, which is produced when the emu is alarmed, angry and threatening. Aussie always felt pretty safe and calm around me, so I only heard this on a few occasions, such as when a strange dog would approach us in the field, or a reckless cat or raccoon would enter our yard, snooping around the chickens. Aussie didn’t like that. He was sort of the hens’ “big brother”. Emus can be pretty aggressive. He would raise himself up as straight and tall as possible and expand his chest and neck, looking very formidable, and charge. If the cats or raccoons, or dogs, hadn’t wisely run off, they would have received a very powerful kick. Emus have sharp claws, so a kick can cause serious damage. I’ve seen videos on YouTube of people, who were foolish enough to get into a pen with emus who didn’t know them, getting chased around by an angry, growling, kicking emu.

When he was closely interacting with me, the most common sound he would make was what I called his affection, or “I love you daddy” sound – a continuous series of quiet, high-pitched little ticks, or “pops”, like small bubbles bursting in his throat. He’d use a little louder, more rumbly/poppy version of this when he was looking for me or calling me.

Now, here’s what I mean about “levels of potential”. Aussie would quite naturally, spontaneously and astutely engage in behaviors with me that would only work with a human, which he would never have engaged in with other emus. For example, he couldn’t open the yard gate, but he knew I could. So, when he wanted to go for a walk/run in the field, he’d let me know, just like a dog would. If I was in the house, he’d actually “knock” on the sliding glass door with his beak. There were three different doors in the back, but he had figured out that this door was closest to most of the house and I’d be most likely to hear him. Just for good measure, he’d also rumble loudly – not the angry growl, just a loud rumble. If I was in the yard, he’d run up to me, rub his head/neck on me, then run to the gate. He’d go back and forth this way a few times to let me know he wanted to go out. As I was opening the gate, he’d jump up and down, making another kind of sound, his “happy rumble”. You wouldn’t have to be an emu expert to recognize that he was feeling joy in the expectation of going out to run. During most days, I kept a large dog harness on him, so that I could easily attach a sturdy leash. I had to leash him when we went out because emus don’t understand and follow orders and, like a cat or an overexcited dog, he would have just run off to the field, which would have been dangerous. After we crossed the street into the field, I’d unleash him, so he could run to his heart’s content. He never left the field, and, in fact, never got too far from me. It wasn’t that he was being “good” or “obedient”, just that he naturally didn’t feel comfortable being too far away from me. Emus travel with the mob (the term for a group of emus). Even though it was just the two of us, Aussie and I were our own little mob. Plus, it seemed that Aussie never really got past the fact that I was his dad and he was my chick. So Aussie never let me get out of his sight.

Another example. Aussie saw me hold the chickens, and he saw the cat and, especially, the dog sit on my lap. I say “especially the dog” because Aussie and my border collie mix, Deco, had the same kind of mild jealousy/competition for my attention that two dogs in the same home often do. So, Aussie also wanted to sit on my lap, which presented a bit of a problem, for obvious reasons. It was manageable while he was still a smallish teenager, but even then he was big and gangly, with those long legs and sharp claws. I had to wear my sturdy Levis. I’d help him up and he’d sit down with his legs folded under, as if he was sitting on the ground. He’d lay his head on my chest, just below my chin, and make his popping “I love you daddy” sounds. He loved for me to run my fingers through the feathers, which are like rough but soft fur, on his back. It was similar to a preening action. Often, he’d go to sleep that way.

As he reached adulthood, that method was no longer feasible. So I had to devise and train him in a new method. I used a lounge chair, with the head end elevated and the foot end sloped down to the ground. I’d sit with my back against the elevated top and my legs to either side of the chair, leaving open space on the chair between them. Aussie would step onto the sloped bottom, then sit down between my legs, then roll a little to the side and extend his legs down the bottom of the chair. So it was just his body, on its side, lying lengthwise on the chair between my legs. Then he could still lay his head on my chest. I’m sure it would have been quite a comical sight for any visitor to see this bird, the same size as me, lying on top of me, sleeping peacefully as I preened his feathers. Sometimes I’d turn on the radio to some nice soft rock and we’d both go to sleep.

It took about a week to fully train him to the point that he could easily position himself, and to feel comfortable in that position. It’s not a natural resting position for an emu. Emus don’t typically lie on their sides with their legs extended. It would make them vulnerable in the wild. But Aussie trusted that I wouldn’t let anything happen to him, so he felt he could do it. He adapted and it worked. He got what he wanted; he had the same lap-sitting privileges as dog. So there, Deco.

Most people think of emus as just big, mentally unimpressive birds that are only capable of living one kind of life in one kind of wild environment, behaving only on instinct, and that’s the only way they can be happy, the only way they should live. Our relationship demonstrated that this is not true. Aussie was smart, adaptable and happy. My friend and I saved him from unnecessary euthanasia. He lived a very rich and fulfilling life with me, at the same time enriching my life, educating me and expanding my understanding of animals.

But the time came when my life had to take other directions and I could not devote the time and attention necessary to properly care for Aussie. So I contacted a friend with a bird ranch, who I knew had a mob of emus living in a nice open habitat on the ranch. It was time for Aussie to explore his own new horizons and have a new, equally fulfilling life with his own kind, hopefully to become a integral member of the mob, find a mate and become a daddy himself. I knew he would receive the best of care. My friend was more than happy to provide Aussie with a new home. We went through a several-day process of introducing Aussie to the other emus, helping to integrate him into the group and find his place. I could tell that meeting the other emus was an exciting experience for Aussie. At first, it was just a little scary and he was reluctant to leave my side, but eventually he was ready to part ways with me and begin to enjoy his new life, expressing a new level of potential.

Modern-day Dinos

It has been generally known for some time that birds are descended from dinosaurs. There are some paleontologists and ornithologists who say that birds are dinosaurs. My friend with the bird ranch took me to another friend’s ranch. This guy had several cassowaries. The cassowary is the second largest bird by weight. It is also the most aggressive and dangerous of the ratites. They are large, heavy, strong and intolerant/quick to anger. They can deliver an incredibly powerful kick that can kill a man, and they have big, sharp beaks. They have large head crests and are really magnificent. When we visited, the owner took a pail of fruit (their food) and we walked to the fence of their enclosure. They were out of sight in a grove of trees. He banged on the pail, and suddenly this group of cassowaries burst out of the trees and came running across the field in our direction. I swear I was watching a group of bipedal dinosaurs running toward us. It almost made me want to flee. It was one of the most incredible and exciting sights I have ever witnessed. I’m now sure I know just what dinosaurs were like. I’ve seen them in real life. No need to visit Jurassic Park.

So, every time you look at your bird, remember his noble lineage. And remember, I get you and I get your bird. If you need to get away for any amount of time for any reason, I can make sure your modern-day dino gets the best of care while you’re gone.